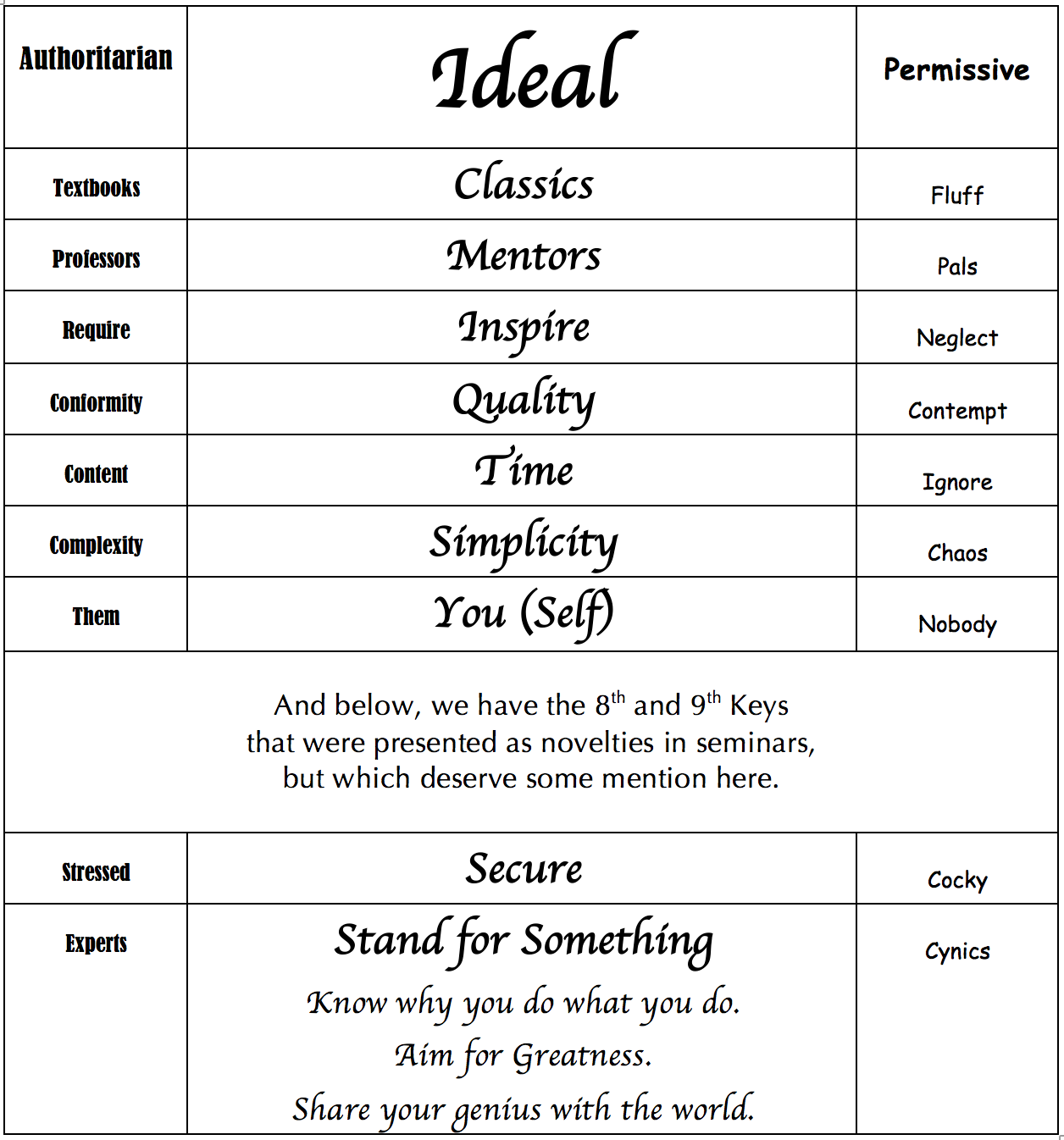

There are seven principles of successful education; when they are applied, learning occurs. When they are ignored or rejected, the quantity and quality of education decreases. Whatever the student’s individual interests or learning styles, these principles apply. These ideas are perhaps best communicated with a counterpoint idea to help elevate it to the degree of emphasis that makes the most difference. The “original” 7 Keys were taught with a counterpoint of Authoritarian ideas that compete with the ideal. We have found that there is an equal and opposite “Permissive” idea that also competes, and that will be shown in parenthesis. (For more information on The New 7 Keys, click here >>)

And whatever your role in education—home, public, private, higher education or corporate training—the application of any and eventually all of the Seven Keys will significantly improve your effectiveness and success.

In a Nutshell

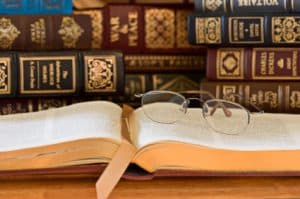

1. Classics, not Textbooks (or Fluff)

No one can deny the value of a great idea well-communicated. The inspiration, innovation and ingenuity inherent in great ideas elevate those who study them.

No one can deny the value of a great idea well-communicated. The inspiration, innovation and ingenuity inherent in great ideas elevate those who study them.

Great ideas are most effectively learned directly from the greatest thinkers, historians, artists, philosophers and prophets, and their original works. Great works inspire greatness, just as mediocre or poor works usually inspire mediocre and poor achievement.

The great accomplishments of humanity are the key to quality education.

This first key means that in pursuit of a transformational education, in preference to second- or third-generation interpretations, we study original sources — the intellectual and creative works of the world’s great thinkers, artists, scientists, etc., in the form they were produced.

2. Mentors, not Professors (or Pals)

The professor/expert tells the students, invites them to conform to certain ideas and standards, and grades or otherwise rewards/punishes them for their various levels of conformity.

The professor/expert tells the students, invites them to conform to certain ideas and standards, and grades or otherwise rewards/punishes them for their various levels of conformity.

In contrast, the mentor finds out the student’s goals, interests, talents, weaknesses, strengths and purpose, and then helps him develop and carry out a plan to prepare for his unique mission.

Various types of mentors are present at different levels of a person’s progress and in different stages of life.

In education, the value of a liberal arts mentor cannot be overstated. Parents and teachers who apply the Seven Keys can be an effective part of the mentoring of a student in the early phases of learning, and help prepare the individual to fully take advantage of the influence of later mentors that will be formative for continued development and achievement.

3. Inspire, not Require (or Neglect)

None of the keys is as highly celebrated and as poorly applied as this one. This is perhaps the least understood and least practiced of the Seven Keys. It is probably the single most important element of Leadership Education.

None of the keys is as highly celebrated and as poorly applied as this one. This is perhaps the least understood and least practiced of the Seven Keys. It is probably the single most important element of Leadership Education.

There are really only two ways to teach—you can inspire the student to voluntarily and enthusiastically choose to do the hard work necessary to get a great education, or you can attempt to require it of them.

Most teachers and schools use the require method, and others use an enlightened “ignore” tactic to try to urge the student to own their education.

Great teachers and schools pay the price to inspire.

Instead of asking, “what can I do to make these students perform?” the great teacher says, “I haven’t yet become truly inspirational. What do I need to do so that these students will want to do the hard work to get a superb education?”

4. Structure Time, not Content (or Ignore)

Great mentors help their students establish and follow a consistent schedule, but they don’t micromanage the content.

Indeed, micro-management has become one of the real poisons of modern education. Great teachers and schools encourage students to pursue their interests and passions during their study time.

Of course, this principle is applied differently at different levels of student development.

Phases

There are 4 phases of learning: Core Phase, roughly ages 0-8; Love of Learning Phase, roughly 8-12; Scholar Phase, roughly 12-16; and Depth Phase, roughly 16-22.

Beyond this come the Applicational Phases of Mission and Impact, where we each set out and accomplish our unique missions in life, and fulfill our role as societal elder and mentor to the rising generation (For more on these phases, click here; also see our book Leadership Education: The Phases of Learning for an in-depth treatment and loads of ideas and how-to’s.)

During Core Phase work times and play times are scheduled, with children allowed to choose their own subjects of play during play time. As they get older, play includes reading, math and other subjects that students choose to engage for fun.

At the beginning of the Love of Learning Phase a student might choose a structure of 1 or 2 or 3 hours a day of set study time; it is important that the student choose it, and that the mentor help the student learn accountability for his choice.

If the student won’t choose it, you haven’t inspired him yet—get to work. Don’t fall back into requiring. Pay the price to inspire, and trust the process–it’s the only way to get the result of the student owning their role as a self-educator.

By the early Scholar Phase a student will likely be studying 6-8 hours a day on topics of their deepest interest. During the Scholar and Depth Phases, the student increases the structured time and goes into more depth.

By the early Scholar Phase a student will likely be studying 6-8 hours a day on topics of their deepest interest. During the Scholar and Depth Phases, the student increases the structured time and goes into more depth.

A more detailed treatment of this process and the ideal cooperation between mentor and student is found in chapter 6 of Leadership Education: The Phases of Learning.

5. Quality, not Conformity (or Contempt)

With the student feeling inspired and working hard to get a great education, the mentor should give appropriate feedback and help.

With the student feeling inspired and working hard to get a great education, the mentor should give appropriate feedback and help.

But the feedback should ideally not take the form of common “grading”, but rather personalized feedback, commenting on the particular strengths of a work, including clarity of expression, original thought, technical precision, correlation of principles and ideas, effectiveness of argumentation or other reader appeal, etc.

These are clearly directed toward the evaluation of a written work, but similar concepts can be adapted for feedback on other products of a student’s scholarly efforts, be they organizational, artistic, personal, interpersonal, innovative, etc. Great teachers and schools reward quality–quality work and quality performance.

In the early phases emphasis is placed almost exclusively on positive feedback; as the student matures (usually after puberty), more technical critiques become valuable and usually preferred by students as they strive for excellence.

In late Scholar Phase and Depth Phase, anything less than high quality is not accepted by the mentor as a completed work; instead, the student is coached on how to improve it and sent back to work on it—over and over again until excellence is achieved.

For example, for years (when teaching college-level students) we utilized a two-grade system: “A” and “DA”, which mean Accepted and Do it Again. Great teachers inspire quality, demand quality—and they coach the student on how to achieve it.

6. Simplicity, not Complexity (or Chaos)

The more complex the curriculum, the more reliant the student becomes on experts, and the more likely the student is to get caught up in the Requirement/Conformity trap.

The more complex the curriculum, the more reliant the student becomes on experts, and the more likely the student is to get caught up in the Requirement/Conformity trap.

This leads to effective follower training, but is more a socialization technique than an educational method.

Education means the ability to think, independently and creatively, and the skill of applying one’s knowledge in dealing with people and situations in the real world.

Complex systems and/or curricula usually lead to student frustration and teacher burnout as personalization is at a minimum and performance requirements are pre-determined.

Great teachers train great thinkers, and great leaders, by keeping it simple: students study the greatest minds and characters in history in every field, write about and discuss what is learned in numerous settings, and apply what is learned in various ways under the tutelage of a mentor.

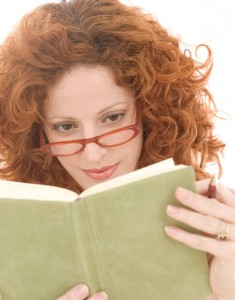

7. YOU, not Them (or Nobody)

If you think these principles are exclusively or even primarily about improving your child’s or student’s education, you will never have the power to inspire them to do the hard work of self-education.

If you think these principles are exclusively or even primarily about improving your child’s or student’s education, you will never have the power to inspire them to do the hard work of self-education.

Give serious focus to your education, create an environment where curiosity is activated, learning is facilitated and excellence is modeled, and invite them along for the ride.

Read the classics in all fields, find mentors who inspire and demand quality, structure your days to include study time for yourself, and become a person who inspires great education.

A parent or teacher doesn’t have to be an “expert” to inspire great education (the classics provide the expertise), but he does have to be setting the example.

Conclusion

The question we’re asked the most is “How do you actually do this?” In general, the people who ask this haven’t become avid students of the classics.

Perhaps the most difficult part about mentoring the classics is knowing which books to recommend and then having something to say about them in discussions with students. So that is where we begin: Get reading.

For tips on getting started, click here. For a step-by-step guide, and suggested reading lists for various ages, see A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the Twenty-first Century. This book gives a more detailed overview of the philosophy and concepts of Leadership Education, and the Appendices offer practical helps for how to get off the conveyor belt.

Once you’ve read five classics in math, five in science, five in history, and five in literature, you won’t be asking that question anymore. Instead, you’ll be asking different questions. Better questions. Lots of them.

Read the classics in all fields, find mentors who inspire and demand quality, structure your days to include study time for yourself, and become a person who inspires great education.

A parent or teacher doesn’t have to be an expert to inspire great education (the classics provide the expertise), but he does have to be setting the example.

There are many resources on this site to help; you can also find support through formal mentoring services, informal groups and clubs, and among the people you know!

The more you know about the principles of Leadership Education, the more confident you will feel about your ability to personalize them for yourself and your family.

If you’re unsure about how to proceed, don’t hesitate to drop us a line. There is so much support and information available, and we’ll be happy to point you in the right direction.

Good to have you along on the journey. We all benefit from each other’s participation and progress in this process.

We are so optimistic for our future as we see the impact individuals are making in their homes, families and communities. Together, we will change the world!